This story, aired on Oklahoma’s PBS station KOSU on Feb. 1, talks about a national effort to map “heat islands” in major U.S. cities. Austin, Houston, Dallas, and El Paso were among the original 14, with Laredo added this year.

Although The Loop included a story on heat islands last summer, this story takes a little different tack; it’s about determining where heat islands exist, and then possibly addressing the problem.

A little review: Heat islands are pockets of a city—sometimes large areas—that are as much as 10 degrees hotter than the rest of the city. They tend to be worse in urban areas due to the number of buildings, roads, and other impervious cover. They can also be a problem in new subdivisions where houses are close together and there is little mature vegetation. The problem can be addressed in a number of ways, the chief methods being creating green spaces, leaving mature trees in place and planting more, reducing impervious and/or dark cover, incorporating green roofs, and installing reflective roofs. For more on these practices, click on the EPA’s discussion here.

As we move into the hottest part of the year, it might be good to think about how San Marcos is doing in addressing the heat island effect. Clearly, one of the best things we have going for us is the San Marcos Greenbelt. As an official Tree City, we can also be proud to be among the roughly 3,500 cities in the country that have been recognized for their efforts in growing and maintaining their tree cover. Finally, the San Marcos River and the vegetation growing along its banks make our city more livable than it would be otherwise. But is there more that we can do?

Where are the hot spots in our city? Are certain neighborhoods impacted more than others? If so, is there anything we can do to mitigate the problem? These questions will only become more important as San Marcos grows and temperatures continue to climb.

Written by Susan Hanson, Editor, The Loop

Article by

Britny Cordera, KOSU, Stillwater, OK

Climate change, driven primarily by burning fossil fuels, pushed temperatures so high last year that scientists were astounded when 2023 became the hottest year on record. Communities like Oklahoma City are now preparing for a future with extreme temperatures by understanding which areas are the hottest.

Last year, Oklahoma City joined 14 other cities in a national project through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to map where heat lingers in neighborhoods. Oklahoma City’s Office of Sustainability, in partnership with the University of Oklahoma, and other environmental organizations, recruited volunteers to act as “citizen scientists” to help researchers gather key data.

Those citizen scientists attached air quality and heat monitoring sensors to their cars to take air and temperature readings of the hottest neighborhoods in Oklahoma City on an August day last year.

Understanding where heat pockets persist in communities is the first step to cooling those places down — and protecting residents from heat illness. Hongwan Li, an assistant professor in the College of Public Health at the University of Oklahoma, researches air quality and helped collect data last summer.

“If we want to take a deeper look for the heat stress like in our communities, community-based is the most appropriate way to understand the heat stress better,” Li said.

The data from the sensors last summer showed that downtown Oklahoma City was 15 degrees hotter than the outer edges of the city, like neighborhoods near Lake Stanley-Draper in the southeast.

Sarah Terry-Cobo, associate planner for Oklahoma City’s Office of Sustainability, led last year’s heat mapping efforts. She was surprised to find out that Mesta Park – with its large sycamore and oak trees that tower over houses – was one of the hottest areas in Oklahoma City.

“A more affluent area like Mesta Park has a lot of older tree canopy that’s intact,” Terry-Cobo said. “And that, you know, is still pretty hot compared to some of these other neighborhoods that we were expecting to be very hot.”

Trees don’t always provide enough cooling because heat gets trapped in roofs, roads, and sidewalks creating what’s called the urban heat island effect.

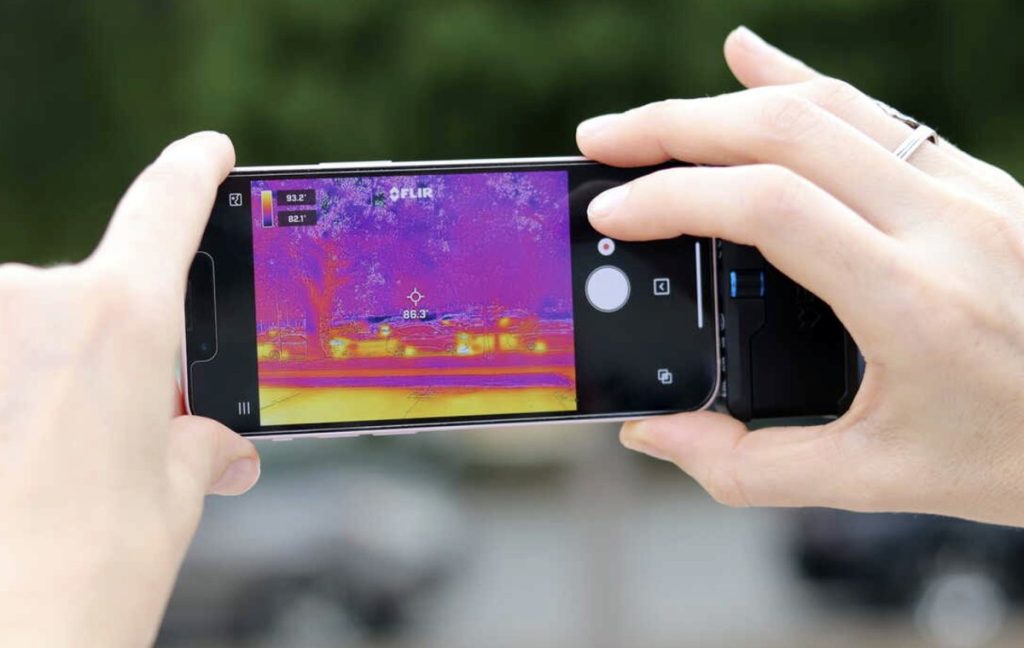

Terry-Cobo walked around downtown Oklahoma City that rainy, humid August day capturing thermal images on her phone. The high for the day reached 98 degrees.

The prairie habitat at the Myriad Botanical Gardens in Oklahoma City, for example, had cooler temperatures than the concrete that makes up the core of the city. Thermal imaging put the sidewalk at 93 degrees while tree shade was at 85 degrees.

“What we’re seeing right now in the Myriad Gardens is a great example of a potential cooling strategy for urban heat islands,” she said.

Cooling strategies can come from understanding the hottest parts of urban areas. Since 2017, NOAA has funded the Climate Adaptation Planning and Analytics Heat Watch program (CAPA) to help organize and provide the equipment and results to over 60 communities across the U.S. and internationally.

Joey Williams, the project manager for CAPA Heat Watch, said heat mapping started to help people learn about where extreme heat impacts their lives, and to help cities come up with strategies to address it.

“As the threat of heat continues to rise, people become more aware that heat is an issue and life threatening and it affects different people differently,” Williams said. “Having this kind of awareness that that’s an issue can be a lifesaver.”

Kansas City, Missouri used its heat mapping data from 2021 to understand where the city lacked tree canopy.

Andy Savastino, chief environmental officer with the city said that helped inform a new policy to preserve the city’s tree canopy.

“Now, any time a developer wants to come into areas where there is an old growth forest, our tree preservation ordinance, which we never had one before, applies so that there is a requirement for developers to replace a percentage of the trees they take down,” he said.

The city of Little Rock, Arkansas found during its heat mapping project last August that the hottest parts of the city didn’t cool off at night. Lennie Massanelli, the sustainability officer for the city, said that meant temperatures in the morning were hotter than the afternoon.

“At the very beginning of the day, the 6 to 7 a.m. map showed the hottest pockets of Little Rock, where heat just kind of stayed in one place,” she said.

Oklahoma City’s heat mapping campaign found the city needs more trees and fewer parking lots to help cool off neighborhoods during the hottest months.

Oklahoma City’s sustainability office is developing a guide book this year to help city leaders determine the best ways to adapt to extreme heat. Terry-Cobo hopes that will include everything from changing zoning laws for parking to reclaiming native habitat wherever the city can — all in an effort to cool down some of the hottest parts of the city.