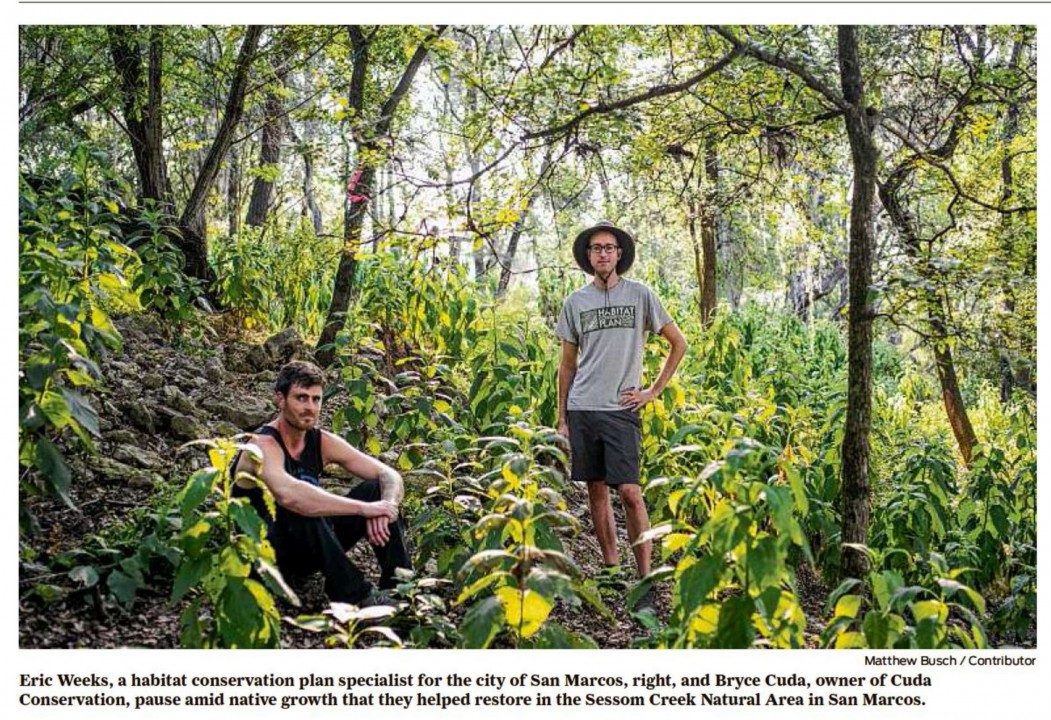

Picking his way through layers of brush, branches and leaves, Eric Weeks removes some stringy vine from the side of a tree, discards it on a trail and reaches up to yank off a bit more before moving deeper into the woods.

It’s a “nasty invasive” plant species called cat’s claw vine, said Weeks, a habitat conservation plan specialist for the city of San Marcos.

And while the vine is a concern to him because it constricts trees, the objective of this trek into the Sessom Creek Natural Area is just up the slope. There he leans over a large spot covered in low, leafy plants, pulls out a clump and tosses it aside.

“This is the purple trailing lantana,” he said.

Generally referred to simply as the purple lantana, the invasive plant native to South America is threatening ecosystems in places such as San Marcos’ Sessom Creek Natural Area, whose 14 acres support an array of plant and animal life, while its creek – named for its natural area – winds its way to the San Marcos River.

Sessom is a welcoming green space in the midst of housing complexes and parking lots, but this purple plant, among the most recently discovered invasive species in Sessom, has worn out its welcome.

Weeks knows this place well, having looked after Sessom since 2018. At that time, the area looked different. Invasive plant species, which overpopulate and harm natural ecosystems, have run amok in San Marcos. So Weeks and an army of other organizations, contractors and volunteers are working to get rid of them all.

And there’s a lot to get rid of. Besides the purple lantana and cat’s claw, there are the tree of heaven, native to China, and the elephant ear, which is found in tropical climates.

Purple lantana, whose pretty purple flowers have proved attractive to residents and developers, spreads fast, jumping from private gardens and overrunning entire areas of native Texas nature.

Commercial nurseries and big-box stores often sell purple lantanas, much to the frustration of Weeks and other conservationists, particularly since there are other plants suited for Texas that offer similar qualities.

Why reject it?

Purple lantana thrives at others’ expense, preventing native species from surviving by blocking their sunlight. As a low-growing plant, it inhibits smaller trees that are just starting to rise.

“It completely covers the ground, and it will block the growth of whatever native plants are trying to grow there,” said Melani Howard, the habitat conservation plan manager in San Marcos for the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Program. “It can spread very quickly and can cover acres and acres of ground.”

The plant is also heat and drought resistant, enabling it to survive in South Texas, and it blooms before native trees do and has prolific seeds that spread faster. Plants like the purple lantana developed certain characteristics from where they originated, which serve them well in this region’s environment.

“I think of a natural area as native, as serving its ecosystem,” Weeks said. “It has a purpose for all the wildlife habitat. And then you have this invasive here. And it takes away all those services that the ecosystem previously provided.”

Birds will often spread lantana seeds, or winds will carry them through the forest. The runoff from rain can also spread them. Planting an invasive species such as the purple lantana in a yard risks spreading it not only to neighbors but everywhere.

And while some say the purple lantana has benefits, notably as a source of nectar for the monarch butterfly, considered a candidate for the federal endangered species list, Howard said such benefits are not worth their negative impact on this region’s ecosystem.

“The purple lantana may attract butterflies to your yard, but the nectar it provides doesn’t have the same component of nutrients that a native plant would have,” she said.

Moreover, she said the entire ecosystem serves the monarch butterfly and would be healthier without the invasive lantana.

“It’s also a certain combination of native plants, so you are not only providing nectar, but the habitat and a place for them to lay their eggs. That’s when you are supporting the complete cycle for the butterfly. A purple lantana by itself wouldn’t do that.”

What you can do

Learning what is native to the environment is key to eliminating invasive plants, but knowing whether a plant you’re buying is invasive can be challenging.

Doing so can be made more difficult by the reality that there are horticulturalists and developers who encourage using nonnative plants for landscapes, Howard said.

In San Marcos, the Discovery Center – an interpretive resource for the city’s parks and rivers – holds a biannual native plant sale as a way to nudge residents in the right direction. At the center, alternatives to the purple lantana include the Texas lantana, a similar native plant that does not overpopulate.

“The Texas lantana is still low to the ground,” said Weeks, who is a coordinator for the Discovery Center. “It’s just a bit wider, more upright, and you have a yellow-orange bloom instead.”

And for people who really like purple, Weeks recommends the Greggs mistflower, a 2-foot-tall perennial that monarch’s settle on for nectar. And there are many others available.

Rewarding experience

Bryce Cuda pulls out big clumps of purple lantana from the soft earth and throws them on a pile. As he looks over the expanse of plants in front of him, the task seems never-ending.

The 29-year-old is a contractor for the Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan. Accompanied by his dog, Snugs, Cuda is constantly cutting down invasive plants in San Marcos.

“Once you learn about an invasive and you see it for the first time, it’s like you see it everywhere,” Cuda said. “You can’t unsee it, and it bothers you.”

Sessom Creek Natural Area is looking good. There’s an entire area of the park with only native plants, long grasses, floppy flowers and a small path winding through. The invasive tree that had overpopulated the space has been reduced to just one off the trail. It’s an exciting result for Cuda and Weeks.

But there’s still much to do, Cuda said. Just up the hill, someone recently dumped a pile of dead plants, which could spread invasive species downhill when it rains. For the conservationists, it’s another frustrating example at the heart of their work. Such feelings don’t last long, though.

“It’s great finding an area where you can say, ‘OK, this is a problem,'” Weeks said. “Let’s work toward it. It’s a rewarding experience.”

Elena Bruess writes for the Express-News through Report for America, a national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms. [email protected].