Trail Notes: In Praise of Bees

Popular as they are for recreation, our natural areas are also important for wildlife conservation, especially as the city grows and habitat shrinks. Hikers and others who use the trails frequently see the creatures that benefit from this protection—deer, foxes, skunks, snakes, and a host of bird species, including the endangered golden-cheeked warbler. What visitors to the natural areas may not notice, however, are the myriad insects that also live there.

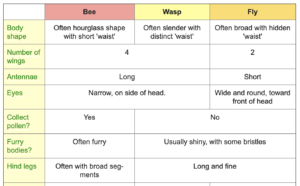

Chief among these are bees, many of which are now threatened. Determining what sort of bee you’re looking at, though, isn’t always easy, particularly since some resemble flies or wasps more than they do the stereotypical bee. Aussiebee.com offers this chart as a means of telling the difference.

But knowing these differences is just a start, given that our state is home to 800 species of native bees in six families: bumble bees, plasterer bees, miner bees, sweat bees, oil-collector bees, and leaf-cutters. Obviously missing from this list is the honey bee, which is not native to the United States.

So what type of bee is a hiker likely to encounter on the trail? There’s no predicting that, but one to keep an eye out for is the iconic American bumble bee, which can be identified by the yellow bands above and below its black “waist.” Remember, though, that this is just one of nine species of bumble bee found in Texas. Unfortunately, it is also one of the four species considered “at risk” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

While the European honey bee has been recognized for its important role in pollinating food crops in this country, the bumble bee has not. There’s good reason for that situation to change, as explained by reportingtexas.com, a publication of the University of Texas School of Journalism: “Because of their ability to ‘buzz pollinate,’ or shake loose additional pollen by vibrating their wings, bumblebees make more effective pollinators than honeybees and other species, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.” Their large size, and thus greater surface area for collecting pollen, also enhances their efficiency.

Do these bees pose any danger to hikers? Not really. Like honey bees, bumble bees can sting, but do so primarily in defense of their nest, which is located underground, often in an abandoned rodent tunnel. Also like honey bees, bumble bees are social, but they don’t swarm, and their nests are far smaller, only a few hundred residents as opposed to thousands. On their own as they’re out foraging, bumble bees tend to either ignore humans or simply fly away.

Do these bees pose any danger to hikers? Not really. Like honey bees, bumble bees can sting, but do so primarily in defense of their nest, which is located underground, often in an abandoned rodent tunnel. Also like honey bees, bumble bees are social, but they don’t swarm, and their nests are far smaller, only a few hundred residents as opposed to thousands. On their own as they’re out foraging, bumble bees tend to either ignore humans or simply fly away.

Humans, on the other hand, have put real pressure on bumble bee populations in a number of ways: through the use of neonicotinoids and other pesticides, monoculture farming, and the loss and fragmentation of habitat.

As the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation notes, “The loss of habitat to development, agriculture, and a changing climate is likely having a profound effect on all wild bees. Native prairies and grasslands are ideal for bumble bees, yet nearly all North American prairies and grasslands have been lost to land conversion, and what remains is heavily fragmented.”

In reclaiming and maintaining these types of landscapes–along with woodlands, brush, and riparian areas—the San Marcos Greenbelt Alliance and City of San Marcos are contributing to the preservation of not just bumble bees, but to a host of other tiny but necessary creatures.

Written by Susan Hanson, a member of the SMGA board and chair of the Outreach Committee.