There are the predictable signs, like the incremental change from green to gold on the cedar elm and soapberry trees in the backyard woods. Sometimes the Mexican buckeye turns gold as well, and every now and then, we see a little red on the several crape myrtles that ring our house. But this year, there was no predicting the exuberance of fall, which seemed to arrive all at once.

There are the predictable signs, like the incremental change from green to gold on the cedar elm and soapberry trees in the backyard woods. Sometimes the Mexican buckeye turns gold as well, and every now and then, we see a little red on the several crape myrtles that ring our house. But this year, there was no predicting the exuberance of fall, which seemed to arrive all at once.

My husband and I first noticed this fact when, driving to church one Sunday night, we were wowed by the sudden sight of an electric gold tree—what writer Annie Dillard would’ve called “the tree with the lights in it.” It sat in the parking lot of the old St. Mark’s Church, now home to two campus ministries. Parking lots are not generally known for their beauty, but this was an exception to that rule.

By the time I went out to snap a picture, the light had changed, and with it, the vibrancy of the tree. So I returned the following morning and found that a friend had done the same. Each of us, it seems, had been captivated by the color of that tree and wanted to record it.

I never found out what kind of tree that was, though the leaves looked a bit like those of a soapberry, or perhaps the non-native Chinese pistache. Both can turn a brilliant yellow in the fall. Someone I know suggested flameleaf sumac because of the shape of the leaves, but those trees are generally more slender and, as their name suggests, turn an eye-popping red in the fall, when conditions are right.

Which leads me to the question at hand: Why were our trees more colorful than usual this year? It turns out, I’m far from the only person to ask about this. Indeed, the question was so common that almost every news outlet in Central Texas dealt with it.

First, I should say, the phenomenon was totally unpredicted. We’re in a drought, after all, and droughts are tough on trees and just about everything else in the environment. As a result, the prognosticators were expecting a less-than-spectacular fall in Texas. But then came November, when we experienced both rain and cold at just the right time. And voila! It was suddenly fall.

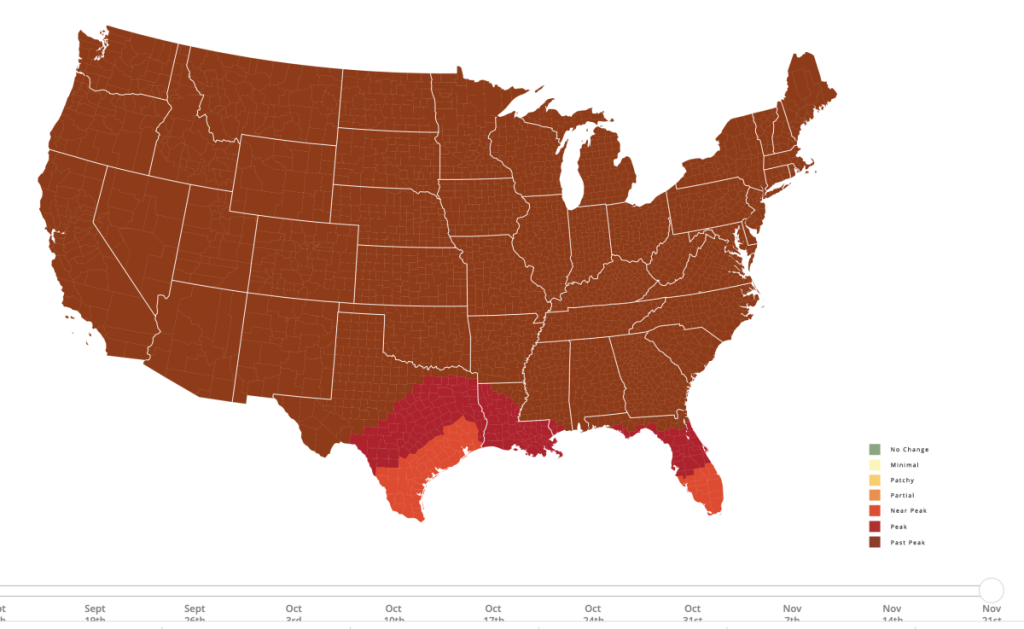

Backing up to review why leaves change color in the first place, we can turn to smokymountains.com, which every year publishes an interactive Fall Foliage Prediction Map for the entire U.S. As the site reminds us, photosynthesis creates chlorophyll, which in turn is responsible for making leaves appear green. Also present in the leaves, though, are compounds known as carotenoids and anthocyanins.

In a nutshell, the color this autumn was due to several things: With cooler weather and shorter days, you get a decrease in the production of chlorophyll, allowing the yellow already in the leaves to be seen. And with cooler weather and more rain, you get an increase in the production of anthocyanin, which gives leaves their red coloring. While the intensity of the display this year came as a great surprise, the timing shouldn’t have. Typically, these processes peak in Texas in mid- to late-November, meaning that in this respect, we were right on track.

If you want to follow the progression of fall color next year, check out the map at smokymountains.com. It’s updated continuously by site users and runs from September through November. As the final map of the season shows, Central Texas is among the last areas in the country to see fall color, reaching its peak in late November.

Written by Susan Hanson, SMGA board member and editor of The Loop.